The Castle Laboratory Tübingen

The Historical Castle Laboratory

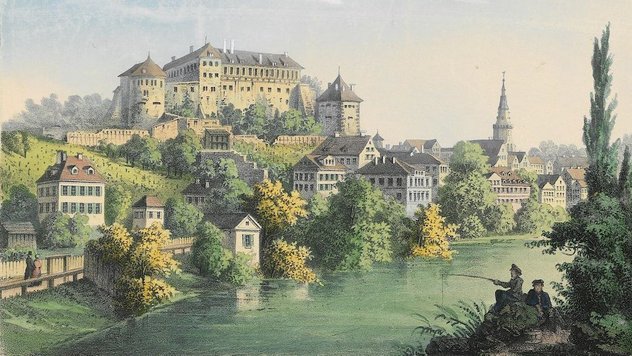

In 1810 the royal head of studies already planned to move the university’s chemical laboratory into the former court kitchen of the Castle of Tübingen. However, the then chair holder Carl Friedrich Kielmeyer refused this request emphatically. After Kielmeyer’s departure the move was carried out in 1818.

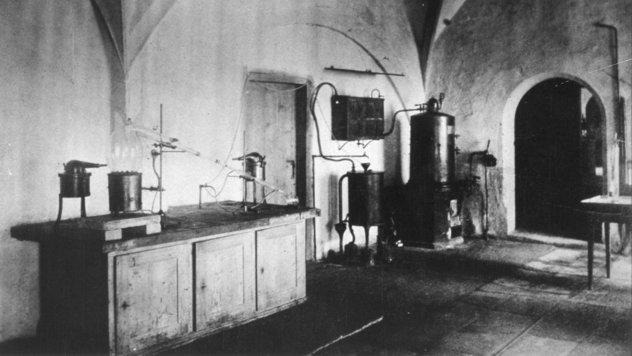

The castle laboratory was, thereby, set up through high costs of 6000 guldens for Gmelin and was even extended to the neighboring former laundry room. However, the remote location on the castle hill as well as the dark and cold walls made the work there unattractive. Thus, for a long time, especially students and doctoral students populated the laboratory in the castle.

In the end, Gmelin handed over the management of the laboratory to Georg Carl Ludwig Sigwart who worked in a neighboring room of the castle laboratory and carried out biochemical research as one of the pioneers of the subject. The castle laboratory became the independent discipline - cradle of biochemistry, especially from 1846 onwards. That year Julius Eugen Schloßberger was appointed as extraordinary professor for applied chemistry, and Gmelin’s general chemistry moved into a new laboratory in the Wilhelmstraße.

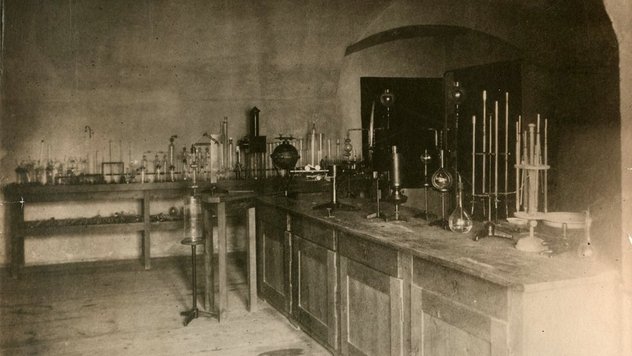

Especially outstanding research was accomplished in the era of Felix Hoppe-Seyler who was appointed as professor in 1861. He examined the red blood pigment and named it “hemoglobin”.

For centuries the hemoglobin research remained a main point of focus of the Tübingen biochemistry. It was also Hoppe-Seyler who published the, for a long time, most significant manual about the methods of biochemistry and who founded the first biochemistry magazine. In 1869 his pupil Friedrich Miescher made the groundbreaking discovery of a substance in the castle laboratory which he named “nucleic” – today known as DNA and RNA, the carriers of the genetic information.

Despite all the adversities in the old walls, the castle laboratory was one of the biggest and best equipped biochemical laboratories of its time. The most medicinal faculties didn’t at all yet have their own laboratory for biochemical studies back then. After Tübingen, however, numerous young doctors came from foreign countries to dedicate themselves to this new scientific discipline under the instruction of Felix Hoppe-Seyler.

The number of students and young scientists finally rose so sharply under the instruction of Hoppe-Seyler’s successor Gustav Hüfner that the castle laboratory could not offer enough space anymore. Meanwhile, it also became poor in construction and technology, “no longer in keeping with the demands of modern science”, as Hüfner stated. After long efforts the country was ready to finance a new construction for the physiological chemistry in the Gmelinstraße in 1883.