Significant Scientific Achievements

Textbook of Organic Chemistry

Julius Eugen Schloßberger’s „Textbook of Organic Chemistry “, focusing on physiological chemistry, was very popular and experienced five editions in just ten years from 1850 onwards. It belonged to the very early journalistic examples, in which an overview of the biochemical state of knowledge of the time was attempted. It still shows the orientation of the early biochemistry through its classification by groups of substances.

“Manual of Physiological- and Pathological-Chemical Analysis“

Felix Hoppe-Seyler’s “Manual of Physiological- and Pathological-Chemical Analysis for Doctors and Students” received big significance for the establishment of the subject biochemistry. The manual was long updated after Hoppe-Seyler’s death and appeared in, all in all, ten editions and edits over a span of ten years. In this textbook he precisely described the analysis technique in the laboratory, the mastery of which is the basis for working in physiological chemistry.

Hemoglobin – Research

Felix Hoppe-Seyler’s systematic studies on the red blood pigment which he named „hemoglobin“ belong to his big scientific achievements – hemoglobin as field of research on which his successors continued in Tübingen into the 20th century. That the research of the blood as “life juice” was of special interest for biochemistry is obvious. Friedrich Ludwig Hünefeld was the first person to describe the blood pigment “which contains the air absorbed” in 1840.

How this substance is built up chemically, how it absorbs oxygen whilst breathing and in which varieties it occurs in people and animals are just some of the questions that Hoppe-Seyler followed up in long-term studies. He isolated hemoglobin in a very pure form and could thus start with elementary analysis’, thus examine the chemical composition of the substance. He was the first person to describe the reversible oxygen-binding of hemoglobin and also discovered the derivate methemoglobin.

Hoppe-Seyler also introduced the spectral analysis for the examination of body fluids in biochemistry and, through this method, found out that the same type of hemoglobin has to exist in different mammals’ blood and in peoples’ blood.

Hoppe-Seyler’s successor Gustav Hüfner determined, amongst others, the maximum oxygen binding to the hemoglobin – this figure is still known today under the name “Hüfner number”.

Hüfner’s assistant William Küster also researched the red blood pigment. After his departure from Tübingen in 1903 he even managed to create a formula for the complicated hemin molecule. The formula was later largely confirmed by Hans Fischer through the synthesis of the substance. Fischer received the Nobel Prize for this in 1930 – if Küster had still been alive then, he would have probably received the Nobel Prize with Fischer. He had been nominated for the Nobel Prize in 1913 already.

In order to determine the hemoglobin content in the blood, so called colorimetric methods were applied, the determination of the substance concentration through color comparison. In the color bar hemometer, a hydrochloric acid solution of the blood sample is diluted in the tube located in the middle until the color precisely matches the reference tubes. Hoppe-Seyler also created a hemoglobinometer which, however, was more cumbersome to operate than other devices, so that it did not assert itself.

PICTURES TO THIS TOPIC

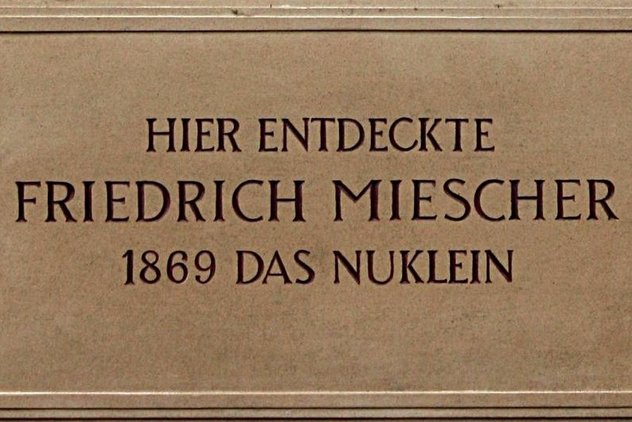

The Discovery of Nucleic Acid

Planning to research the chemistry of individual, simple cells, Friedrich Miescher dedicated himself to the leukocytes, the white blood cells, from autumn 1868 in the castle laboratory. In order to get a hold of leukocytes, he chose a less appetizing, but very productive source: He collected used bandages, so as to wash out the white blood cells contained in the puss.

After extensive examinations, he came upon a completely new type of substance in the nucleuses at the beginning of the year 1869. He named the substance “Nucleic” (pronunciation: nu-cle-ic) – taken from the Latin word for core, nucleus. In order to examine this core substance more closely, Miescher applied the digestion enzyme Pepsin which he won from pigs’ stomachs. With the help of the enzyme, the proteins of the puss cells could be decomposed so precisely that only the pure nucleic was left over.

Miescher carried out elementary analyses with the isolated substance, and could characterize the nucleic as a so far completely unknown cell substance with a high amount of phosphor. He could, however, only speculate about the meaning of nucleic. Today we know that he didn’t discover anything less than the substance in which our genetic information is encoded: the DNA. To date, it carries the term “nucleic” in its name, as DNA or in German DNS stand for “Deoxyribonucleic acid”.

An original preparation from Miescher himself, with isolated DNA, has been obtained and can be viewed in the permanent exhibition in the castle laboratory of Tübingen. It carries the inscription “Nucleic from Salmon Sperm /F. Miescher” and probably originated around 1871, when Miescher continued his examinations of Rhine-salmon in Basel. The publication of his work first took place in 1871 in the fourth volume of Felix Hoppe-Seyler’s “Medicinal-Chemical Examinations” because Hoppe-Seyler was skeptical at first and had to test Miescher’s experiments precisely himself.

PICTURES TO THIS TOPIC

Founding of the “Magazine for Physiological Chemistry“

Over a span of many years Felix Hoppe-Seyler wished there would be an own professional magazine for physiological chemistry. In the 1860s it still lacked in suitable publication options. Therefore, Hoppe-Seyler founded the series “Medicinal-Chemical Examinations” in 1866 with the subtitle: “From the Laboratory for Applied Chemistry in Tübingen”. In this series he published his own studies, as well as the research results of his colleagues in the castle laboratory.

After the publication of a fourth volume, the series was, however, discontinued. The restriction on the Tübingen research seemed to narrow for Hoppe-Seyler. However, the idea of a professional magazine followed him all the way to the new place of work in Strasbourg. In 1877, he finally founded the “Magazine for Physiological Chemistry” as first professional magazine for the field of biochemistry. After his death the magazine was continued as “Hoppe-Seyler’s Magazine for Physiological Chemistry”. Today it is called “Biological Chemistry”.

REDISCOVERY OF THE MENDELIAN RULES

With the name of the botanic, Carl Correns, the rediscovery of the Mendelian Rules is connected. The Mendelian Rules are the inheritance rules which Gregor Mendel formulated in the 1860s, the publication of which didn’t receive any attention at first. Carrying out his cross experiments with plants in Tübingen, Correns noticed that there were exceptions to the Mendelian Rules, and that these had to be explained. He therefore became one of the important driving forces of the late genetics.

Cell Free Fermentation (Nobel Prize for Eduard Buchner)

In 1907, Eduard Buchner received the Nobel Prize for a discovery which he made in 1896 during a visit to his brother’s in Munich. He had occupied himself with the chemical processes during the fermentation before, already, and knew the common theory, according to which the fermentation is initiated through a specific ability of living yeast cells. That is why he was very surprised to recognize blistering when mixing (cell free) pressed yeast juice with sugar which points to fermentation.

Back in Tübingen in the laboratory, he could also prove that extracts from yeast cells can bring about the fermentation of sugar into alcohol and carbon dioxide, and published these finds in the following year. This was a significant step in the history of biochemistry because it proved that only specific substances are needed – enzymes – to initiate complex biochemical processes. A whole living cell is not needed, contrary to what was believed beforehand.

Research on the Citrate Cycle

Studies on the metabolism of fatty acids and the decomposition of citric acids in the body led Franz Koop and his assistant Carl Martius to a complex process which is known as citric acid – or citrate cycle. Many important metabolism paths, also those of the carbohydrates, flow into the citrate cycle. The citrate cycle plays an important role in the energy production, by further degrading the sugar fission product, pyruvate, and feeding it to “combustion” in the so-called respiratory chain.

Together, Knoop and Martius resolved many important steps in this cycle in Tübingen, but misjudged its circulatory character. Hans Adolf Krebs managed to correctly reconstruct the process as circulation. Although he was mistaken about other things, he was rewarded the the Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine in 1953 for the revealing the citrate cycle. Martius and Knoop, who had been dead by this time already, received nothing.

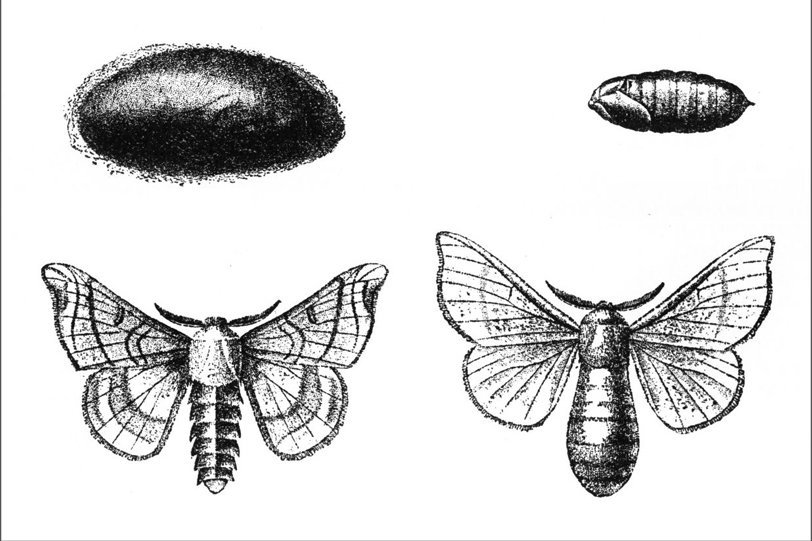

Research on the Insect Hormones and Insect Pheromones

Biochemically, what causes the transformation of the caterpillar into a butterfly? This question was answered by Nobel Prize winner Adolf Butenandt, when he managed to successfully isolate and analyze an insect hormone for the first time – of the “pupation hormone” Ecdyson. His test object was the silkworm caterpillar whose breeding was well known from silk production. Not less than a half a million male pupae were needed, in order to eventually gain 25 milligrams of the pure hormone.

Also using the example of the silkworm, Butenandt could prove in Tübingen and in Munich, until 1959, that insects communicate with each other via neurotransmitters, so-called pheromones. Butenandt and his colleagues managed to, after many years of working on it, isolate the pheromone of the silkworm out of several hundred thousand glands. They thereby made a sufficient amount of pheromone accessible for research for the first time.

Genetic Control of the Embryonal Development (Nobel Prize for Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard)

Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard was a graduate of the biochemistry course at the University of Tübingen and returned to Tübingen after short stays in Freiburg, Basel and Heidelberg. In Tübingen she was initially worked at the Friedrich-Miescher-Institut and, since 1985, researched at the Max-Planck-Institute for Developmental Biology. In 1995, she received the Nobel Prize for Medicine or Physiology alongside Eric Wieschaus for their longstanding research on the genetic control of the embryonal development.

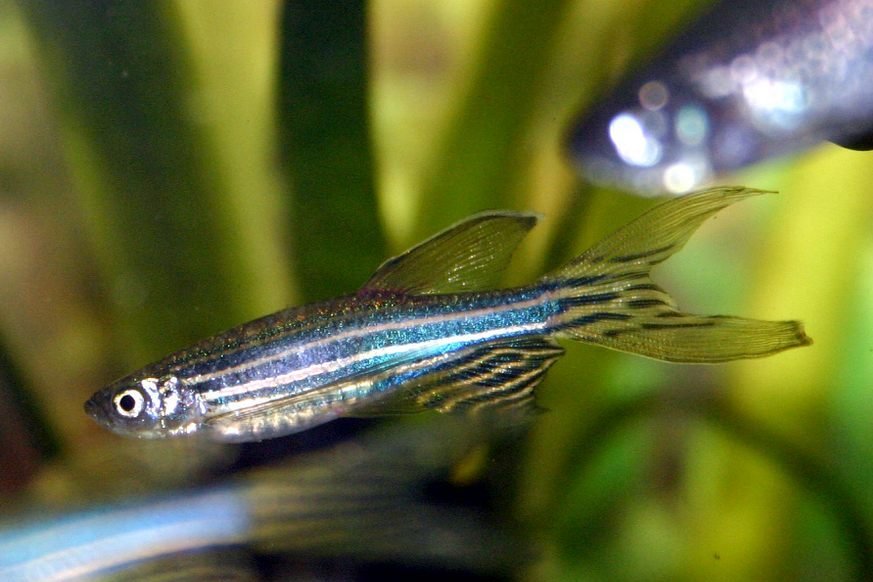

At first, she researched the genes which control the structure of the body in the egg of the fruit fly, and developed a specific theory, how the gene expression in the egg and the embryo is regulated. She later extended the research on the developmental biology of the zebrafish which she established as new model organism in genetics.